Do I Have to Pay Tax When I Sell My House?

When you sell your primary residence, and meet certain requirements, you may be able to exclude all or a portion of your capital gain in the property from taxes. In this article, I am going to cover the $250,000 capital gains exclusion for single filers, and the $500,000 capital gains exclusion for married couples filing joint. However, as financial planners, we have also run into some unique situations where clients:

Live in an owner-occupied duplex and rent one half of the property

Have a home office and have been taking depreciation as a tax benefit

Moving into a rental property and made it their primary residence

For homeowners that fall into one of the unique categories, they may face an unexpected tax consequence when the go to sell their property. They may wrongly assume the large capital gains exclusion associated with selling a primary residence will cover gains and depreciation that was taken on the rental portion of the property.

$250,000 / $500,000 Capital Gain Exclusion

When you sell an asset that is appreciated in value, in most cases you must pay tax on the amount of value that that asset has gained since you purchased it. For real estate, if you have held the property for more than 12 months, you typically have to pay long term capital gains tax on the amount of the appreciation. However, for your primary residence, the IRS offers taxpayers some relief if certain requirements are met. These conditions are that:

The home must be considered your primary residence based on IRS rules

You must have occupied the house for at least 2 of the last 5 years

If you meet these requirements, when you go to sell your house the IRS offers the following capital gains exclusion amounts:

Single Filers: $250,000

Married Filing Joint: $500,000

If you are a single tax filer, meet the primary residence requirements, and the gain in your house is not more than $250,000, you will not pay any tax when you sell it. For married couples filing joint, as long as the gain in the property is not more than $500,000, you will not pay any tax when you sell it. Do not mistake the sales price of the house with the amount of the capital gain. If you are married and sell your house for $600,000, that does not necessarily mean that you are going to have to pay tax when you sell it. If you purchased the property 10 years ago for $400,000, and you sell it today for $600,000, you have a $200,000 gain in the property. Since the capital gain exclusion for married couples filing joint is $500,000, you do not have to pay any tax on the gain when you sell your house.

Calculation of Your Cost Basis

When you calculate the gain in your house, you take the sales price of the house, minus the purchase price of the house, minus the cost of any capital improvements that you made to the house while you owned it, minus any commissions that you paid to the realtor. For example, I'm a single filer and I bought a house for $200,000, 10 years later I sell the house for $500,000. when I lived in the house I made $50,000 of capital improvements and when I sold the house I paid the realtor a 5% Commission.

Since the total capital gain is below the $250,000 threshold, I will not pay any tax when I sell the house.

NOTE ABOUT CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS: You should have documented proof of your capital improvements. Anytime you make major house renovations, you should keep the receipts in case you are ever audited by the IRS and have to justify those capital improvements.

You Can Use The Exemption Multiple Times

This capital gains exception on your primary residence can be used more than once during your lifetime. The only restriction is the exemption can be used only once every two years. For example, let us say you are married and file a joint tax return. You buy your first house for $200,000, and 10 years later sell it for $400,000. In this scenario, you will not pay any tax when you sell your primary residence. Now assume you then take that $200,000 gain and use it as a down payment on your new house and the purchase price of that new house is $400,000, you live in that house for 15 years, and then sell it for $700,000. You will again be able to exclude the full gain in that property when you sell it.

Capital Gains Rule For A Rental That Is Owner Occupied

Here is our first unique situation: It is not uncommon for someone to buy a duplex, live in 1/2 as their primary residence, and rent the other half to a tenant. The question becomes when you go to sell the duplex, how does the capital gains exclusion work since technically it was also your primary residence. This is tricky. In the eyes of the IRS, the duplex is 2 separate properties. The half that you live in is your primary residence, and the half that is rented is actually an investment property. Only the half that you live in as your primary residence is eligible for the primary residence capital gains exclusion. The rented portion of the property is not eligible for the capital gains exclusion.

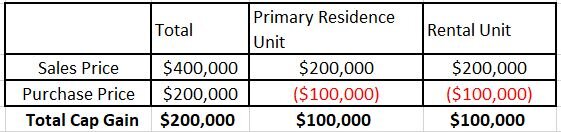

For example, I found a duplex for $200,000, I live in 1/2 as my primary residence and I rent the other half to a tenant. 10 years later I decide to sell the duplex for $400,000. even though I'm a single filer and technically have a $250,000 gain exclusion for my primary residence, that unfortunately will not cover the full gain in the property when I sell it. Here is how I have to allocate the gain between the two units:

The $100,000 gain associated with my principal residence unit is exempt from taxes because it's below the $250,000 exclusion for a single filer. However, the $100,000 capital gain associated with the rental unit, I will have to pay tax on. Since I also owned the house for more than a year, I would pay long-term capital gains rates on the $100,000 which could mean 15% Federal Tax and State Tax. Assuming the State Tax is 5%, I would owe 20% in taxes on the $100,000 gain equaling a $20,000 tax bill.

Recapture of Deprecation

When individuals own rental properties, it is not uncommon for the owner to be taking depreciation on the value of the rental property. Depreciation is a tax strategy which allows you to realize the expense of the property and use those expense to offset income from the property, thus reducing the owner’s tax liability. However, when you sell a property, you have to recapture the depreciation that was previously taken as a tax benefit. Therefore, not only would you potentially have to pay tax on the gain of the rental unit, but you have to factor in that appreciation which is taxed at a different rate than long-term capital gains.

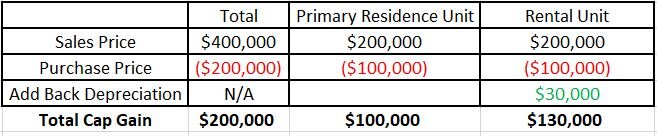

Let us build on the example with the duplex we just discussed. Over the course of the 10 years that I own the property, I took $30,000 worth of depreciation against the property to reduce the tax liability against the rental income I was receiving from the tenant. When I sell the house, the cost basis of my primary residence unit and the rental unit will be different due to the depreciation adjustment. See below:

As you see in the example above, I have a larger gain on the rental unit because I had to add the $30,000 appreciation amount to the gain (or in the accounting terms, it reduced my cost basis by another $30,000). In this situation the $100,000 gain associated with the primary residence unit is 100% excluded from taxes because it is below my $250,000 single filer exemption. However, on the rental unit I will have to pay tax on the $130,000 gain, but the $130,000 is not all taxed at the long-term capital gains rate. The $30,000 in depreciation recapture is taxed at a flat 25% tax rate, whereas the remaining $100,000 and gain is entirely taxed at long-term cap gains rates.

Why does the IRS tax depreciation recapture at a different rate? They recognize that you use the depreciation to offset income that was originally taxed at ordinary income tax rates, which could be as high as 37% or more. So, they are essentially asking you to pay more tax on the portion of the game assigned to the tax deductions you took while you owned it.

A SPECIAL NOTE ABOUT DEPRECIATION: Depreciation recapture is limited to the lesser of the gain or the depreciation previously taken. For example, if you took $100,000 in depreciation against the property but the gain when you sold the property was only $50,000, when you sell the property you have to pay tax on the $50,000 gain, but it will be at the full 25% depreciation recapture rate. You do not have to pay tax on the full $100,000 depreciation recapture when you sell the property.

Moving Into A Rental Property To Avoid Capital Gains Tax

This is another unique situation that we run into sometimes. Individuals that own rental property that has appreciated in value, or sometimes get the idea that if I move into the property and make it my primary residence for two years, all of the gain in that property will then be sheltered by my primary residence capital gains exclusion. The rule of thumb in these situations is if you have thought of it, the IRS has probably thought of it as well, and has probably put some form of restrictions in place. That is unfortunately true of this strategy as well. In 2009 The IRS created a “qualified vs non-qualified use” test:

Qualified uses the period of time that the house is considered your primary residence. Non-qualified uses the period of time that that house was an investment property. The test applies to ownership periods beginning in 2009, and it ultimately determines that even if you have met all the requirements in making that house your primary residence, when you go to sell it the test will determine how much of the gain exclusion you get to apply when you sell the house.

For example, if you rented out a vacation home for 10 years and then you moved into the house for three years as your primary residence, when you go to sell, the capital gains exclusion is limited to 3/13 of the capital gain the property.

Let's assume I buy a vacation home for $300,000, and rented it out as an investment property for 10 years. I move into the house and make it my primary residence for three, but now have decide to sell it for $700,000. Since I am married and file a joint tax return, it is easy to assume I am eligible for a $500,000 capital gains exclusion on my primary residence. However, in this situation I cannot shelter the full gain because the IRS would apply the qualified use test.

$400,000 Capital Gain x 3/13 = $92,307

When I sell the property and realize the $400,000 gain, I am only able to exclude $92,307 from taxes using the primary residence gain exclusion. The remainder of the gain would be taxed at long term capital gains rate and any depreciation recapture would apply.

Selling Your Primary Residence With A Home Office

For an individual that has been claiming a tax deduction for a home office, a word of caution: If you have taken depreciation over the years for the home office, when you sell the primary residence, you will be eligible for the capital gains exclusion, but you will have to recapture the depreciation that you claimed over the years.

DISCLOSURE: This article does not contain tax advice and is for educational purposes only. For tax advice, please consult your tax professional.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.